Race Relations

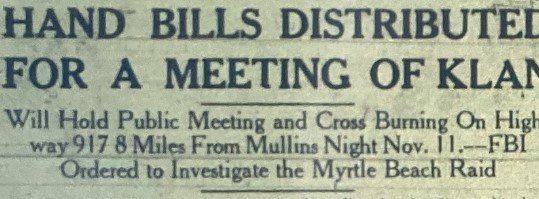

South Carolina retains a notoriously horrendous history regarding race and race relations dating back to its foundation; the relationship among races in South Carolina during the Korean War is of no exception. Life for Black, and African-Americans in Horry County was extraordinarily difficult. It could be said that People of Color in Horry County in the early 1950s often got the short end of the stick, yet they may not have even been given that much. People of color in Horry County, Black, and African-Americans distinctively were deprived of their civil rights and civil liberties on a daily basis. Every aspect of life for Black Americans was purposefully designed to put them at a disadvantage. Racial segregation of schools, businesses, public transport, neighborhoods, beaches, among others settings is just the tip of the iceberg of the injustices that non-white Americans in the county faced with regularity throughout the Korean War and beyond. Racial segregation in the county drastically reduced educational, economic, political, and social opportunities for People of Color across the county, and not only were these Americans being deprived of even the most basic civil rights and civil liberties, but they were virtually shut out of any chance to better their conditions through political means. Article 2, Section 6 of South Carolina's Constitution of 1895 stated that, "The General Assembly may require each person to demonstrate a reasonably ability, except for physical disability, to read and write the English language as a condition to becoming entitled to vote," and that “those registering after January 1, 1898 had to be able to read and write any section of the constitution submitted to them or show that he owned and had paid taxes during the previous year on property in the state valued at $300 or more.” This literacy test virtually eliminated the black electorate, and registration and polling officials openly discriminated against People of Color by providing difficult and complex sections to blacks and then be hypercritical of the registrants' explanations. White Americans could be provided with easier sections, with the explanations graded more indulgently.” Non-White citizens of Horry County who were of voting age were often, not provided with equal, equitable, or adequate education within South Carolina’s schools to pass the literacy test even if discrimination was not an obstacle. [1] In the years leading up to, and during the Korean War the horrid conditions of life for people of color in Horry County were exacerbated with a resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) in the local area. The KKK is an American white supremacist, hate, and terrorist organization that experienced its third wave of prominence in the United States during the 1950s and 1960s. The Association of Carolina Klans led by Thomas Hamilton as Grand Master was the most prominent chapter of the KKK in Horry County, and their presence in the local area was exacerbated by the civil rights agenda of the Truman Administration. [36] The local KKK was notorious for their use of savagery and intimidation against Black Americans in Horry County, and likewise brutality against white Americans was not uncommon. Beatings, torture, lynching, intimidation, and destruction of property were common occurrences, and while the most ferocious of crimes were covered in local news media the majority of hate crimes against locals went unreported, or ignored. The climax of the terror perpetrated by the Association of Carolina Klans culminated in a mass shooting at a local black-owned nightclub in Myrtle Beach called Charlie’s Place in August, 1950. [3][36] A general attitude towards the KKK in Horry County can be summed up in the words of John W. Hardee (likely a alias) who in a letter to Horace Carter (a Pulitzer Prize winner, and owner/author/editor of multiple South Carolina newspapers including The Myrtle Beach Sun), explained his take on the Association of Carolina Klans. Hardee wrote about the KKK claiming that “it’s just a good old Red Blooded American Organization. Organized to support the good Morals of Good American People.” [4] Hardee who idolized the KKK in his letter to Carter did however, have one complaint regarding the local Klan in that he “think[s] the Ku Klux Klan is a very good Organization with only one exception, they are getting too far behind with their work.” [4] Hardee ends his letter with a jab at President Harry Truman writing that “Mr. Truman was going to do away with the KU KLUX KLAN ORGANIZATION in the South Land, but to be sure he was only pouring Gasoline on an Organization of Good Morals and clean Living.” [4] Considering the state of race relations within Horry County during the Korean it is is imperative to remember that while events like the mass shooting at Charlie’s Place, Klan rallies outside downtown Conway, Klan organized motorcades, and cross burnings along The Grand Strand, were happening there were Black, African-American, and other people of color from Horry County actively serving in Korea, and else where across the globe. While there was a KKK motorcade storming through downtown Conway, there were local Black Americans fighting North Korean soldiers in South Korea. While the KKK was shooting at Black Americans at Charlie’s Place in Myrtle Beach there were local Black Americans being shot at by North Koreans on the behalf of those same white Americans that were terrorizing their families back home. Local Black Americans, fought, and died in a desegregated Armed Forces for the first time in the nation’s history, yet when they returned home they were returned to a life under Jim Crow where their skin color took precedent over their sacrifices.

It should be noted that “although Black Americans have typically been the Klan’s primary target, adherents also attack Jewish people, those who have immigrated to the United States, and members of the LGBTQ community.” Practically anyone who was not a white, Protestant, Anglo-American citizen of the United States was vulnerable to the KKK’s draconian tactics, but Black Horry County citizens bore the brunt of Klan violence in the region. [19]

A 1951 letter to the editor of The Field, signed by Chariman A. J. Grove, and Secretary A. W. Stackhouse from The Colored Citizen’s Committee of Horry County helps historians better understand people of color’s lives and social standing in Horry County during the Korean War. In their letter they explained that the time has come that they

should try to enlighten the decent white people of Horry County as to show how we feel towards the white race. Years ago, the Race Path Street was set aside for colored people tp live in and enjoy their homes and religious life. We are still segregated. All the white people you see in our section of town moved in on us (they are welcome), but I’m sure that you can’t name any place where any colored person has moved in on Whites. A few years ago we were given the privileges of voting. We petitioned the Horry County Democratic Part to give us a precinct to cast our vote. We were given Race Path Street. The colored people who are qualified to vote come from all parts of the precinct. During our election certain ones paraded through our section and frightened the women and children. We made no complaint and accepted it without protest, hoping that the good citizens of Conway would give our people protection. The City officials have employed two colored police men who are doing a good job. Thanks to the Town of Conway. Our colored school burned to the ground few years ago and the white citizens came to our rescue and it wasn’t long before we had a better building. And today, we have our own schools, our own churches, our own beaches as well as amusements and our own place to vote. When we vote it is our desire to cast a vote for better government. We have a legal right to serve on jury duty, but we in this County have never asked for such. We are hoping in the near future to be called to serve. However, certain organizations are preaching against our race. We are sure that the intelligent of the white are known that we still want their advice and leadership. We understand that the sales tax was put on to raise money for the better educational facilities for the colored race. We are grateful to our Governor, the General Assembly, and all others who helped. We want to live decently, educate our children, and always remain a race who will work and strive for good government and look to the better class of people for good leadership. God bless your help. [17]

Black Soldiers in Korea

General MacArthur watching the Inchon Landing September 1950.

General Ridgeway c. 1951

Soldier lifting woman at a Korean brothel c. 1951

In the early years of the Korean War racial integration of military units was noticeably sluggish and all-black, or all-white units were still the norm. [9] Integration was often stalled by high ranking military officials, and the late American civil rights activist, and Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States “‘Thurgood Marshall recalled that General MacArthur, who believed that African-Americans were inferior to whites, was the greatest impediment to the Army’s desegregation in Korea.' Things changed rapidly as soon as Truman fired him in 1951” [20a] General Matthew Ridgeway took command of UN forces and actively promoted the desegregation of all units.” [20a] Thus by the end of 1953, more than 90% of African American enlisted men served in integrated units. [20a] However, statistics like these should not be misinterpreted as meaning that integration was a universal phenomena, and “each branch had its own unique path toward ultimate desegregation.” [6] The Army entered Korea with “some segregated and some mixed units, [while] Marine Corps leaders utterly ignored Truman’s desegregation order and entered the Korean War strictly segregated.” [6] Early in the war Black Marines only served in noncombat positions, with half of them acting as stewards. Narratives of Black soldiers from Horry County who were fighting in Korea from have been elusive; records of Black soldiers from neighboring regions of the state are much more common. A Black soldier from Colombia, South Carolina Private 1st Class Richard B. Dinkins, entered a company in the 5th Marine Regiment as the sole Black soldier in his unit. Generally speaking situations such as these went relatively smoothly, and “in Dinkins’s case an awkward moment of silence at this arrival was quickly dispelled when a tall, white Texan invited him to share his shelter. Over the next few months, Dinkins went on to become the best marksman in the company, with an estimated eighty-five kills by the start of December 1950. Echoing the ‘no color in a foxhole’ sentiment that would become gospel in years to come, his company commander noted that on the front lines, ‘we don’t worry about color much up here. They’re all Marines to me.’” [6] Yet, Black soldiers could not evade discrimination while fighting in Korea. Discrimination within their own units was prevalent, but racial intolerance of Black Americans was also widespread amongst Koreans. During the Korean War the United States Military utilized regulated prostitution services for military service men. For many Korean sex workers, engaging with Black soldiers was not worth the societal backlash that came with the act. [16] In Korean society “the women who associated with African American soldiers occupied the lowest ranks in the clubs and bars where servicemen spent their off-duty hours, and these circumstances caused many Koreans to view Korean black children with particular disdain.” [16] Black Americans from South Carolina may have been an ocean away from the Jim Crow Laws and racial segregation that polluted the American Homefront, but they could not escape exclusion, or prejudice that came as a result of the color of their skin.

Black Residents in Horry County

Headline from The Horry Herald (1950)

Headline from The Horry Herald (1950)

Article from The Horry Herald (1950)

Article from The Horry Herald (1950)

Headline from The Horry Herald (1950)

Handbill distributed by the Association of Carolina Klans (1950)

Article from The Horry Herald (1950)

Article from The Myrtle Beach Sun (1951)

While Black soldiers were fighting a war in Korea, Black citizens of Horry County were fighting a war of their own back home. The Carolinas were experiencing a resurgence in the KKK, and Horry County was their biggest target. The expansion of civil rights nationwide partly contributed to the rise of the Association of Carolina Klans, and the local Klan retained thousands of supporters in Horry County. The KKK terrorized citizens of all races in Horry County, but violence against Black residents was more brutal and much more widespread. Floggings, cross burnings, Klan rallies, intimidation, and armed caravans were happening on a weekly basis. The KKK made a point of terrorizing black residents and patrolling black neighborhoods, but they also committed acts of violence against white residents for so much as missing Sunday service. [7] [17] Local newspapers followed Klan news closely, and word of Klan violence in Horry County made national headlines with Life Magazine featuring the Association of Carolina Klans and their crimes twice in 1951. The height of Klan violence in the county took place on the night of August 26, 1950 when a slow moving armed caravan of twenty seven cars (twenty six of the cars bore South Carolina license plates) made its way from Loris towards Myrtle Beach. [4] The caravan rolled through the black neighborhood known as The Hill in Myrtle Beach touting racial slurs, threatening white patrons of The Hill’s black-owned bars and clubs, and intimidating local residents. [4] As the caravan was on its way back to Loris the Klansmen caught word of a verbal threat from the owner of the nightclub Charlie’s Place in The Hill presumably over the radio and diverted their course back towards Myrtle Beach. [17] When the caravan arrived back in Myrtle Beach they gathered outside Charlie’s Place and soon after a firefight ensured with barrage of over 300 bullets being fired into Charlie’s Place with some fire being returned from black patrons of the nightclub. [3] When the dust had settled, and after the caravan had fled a number of black residents were wounded, one person lay dead, and Charlie Fitzgerald the owner of Charlie’s Place had been stuffed in the trunk of a car and taken way. He was beaten, had his ear lobes sliced, and miraculously escaped from captivity. Charlie went to report the incident to the Chief of Police who unbeknownst to Charlie at the time was in the car that kidnapped him. [3] Alternatively the body of a man who laid dead in front of Charlie’s place was draped in full Klan regalia; he had been accidentally shot in the back by one of his fellow Klansmen. [3] When his mask and robe was removed it was discovered that the dead Klansman was none other than forty-two year old Conway police officer James D. Johnson who was still wearing his uniform under his Klan robes. [3]

The raid on Charlie’s Place publicly revealed that the KKK retained a wide reaching and expansive membership where it was very common to see politicians, police officers, teachers, and lawyers among other everyday Americans subscribing to the Klan’s belief system and carrying out acts of violence. While the raid on Charlie’s Place in 1950 was the most consequential act of terrorism by the KKK in Horry County during the Korean War, their presence was ever-present throughout the entirety of the conflict. Black soldiers from the county were fighting in Korea on behalf of their local Horry County community that wanted nothing more than to subjugate, or eliminate their families back home.

Image from The Horry Herald (1950)

The robes in this image are those of the Thomas Hamilton leader of the Association of Carolina Klans being worn by unnamed Klansman. The robe, hood, crosses, and whip were all found in the trunk of Hamilton’s car following the attack on Charlie’s Place. There is a strong possibility that the whip in this image was used on local residents during the Klan’s reign of terror on Horry County during the Korean War.

Article from The Horry Herald (1950)

Article from The Field (1951)