The Local Experience in Korea

Locals from Horry County men and women both served during the Korean War. Some served within Korea while others served elsewhere in Japan, Hawaii, on the United States mainland, and elsewhere. It was a point of pride for locals to see the names of their sons, daughters, neighbors, and friends in the paper describing their efforts in Korea. The news of locals from Horry County was not just confined to South Carolina, for it was not uncommon to see local stories in the national headlines. Life Magazine, Time Magazine, The New York Times, and the Washington Post among other national news outlets covered Horry County news and the exploits of locals in the Korean War. Despite there being a national focus on local news the history of Horry County during the Korean War has been overlooked or merely ignored. The U.S. Military Fatal Casualties of the Korean War for Home-State-of-Record: South Carolina official report retained by the Office of the Secretary of Defense, and the National Archives lists a total of eleven fatal causalities from Horry County in the Korean War. However, further research has shown that some locals who lost their lives in the Korean War have been left off the official record. The cause of this absence within the historical record is unknown, yet the sources and data to confirm that there is indeed a lapse in the official record is widespread and often easily attainable. Nevertheless, the lived experiences of locals veterans of the conflict in Korea whom are both remembered and forgotten are intertwined within the fabric of Horry County’s identity.

The local experience in Korea can be summed up in the 1952 testimony of Pfc. Thomas W. Woodward from Conway, South Carolina describing his first night of combat in Korea. Woodward was a part of the 223rd Infantry Regiment, and in response to being questioned about his reaction to his first taste of combat in Korea, and what was going through his mind at the time he said that:

“At first I wondered what is [sic] was going to be like. Back in basic I listened to Korean vets, and I tried to remember what they told me. I wish I remembered more. It was dark when I arrived at the 1st platoon of Company B, I couldn’t see much. The platoon leader took me around to meet the rest of the fellows. I thought, ‘This is my home for a while.’ ” The same night of his arrival in Korea his company was targeted by enemy mortars, and Woodward explained that “I fell flat on my face without thinking. I thought I was lying in the open. I grabbed the ground. After a while, I wanted to fire back . . .anything [sic] but lie there and wait. I was shaking when it was all over. I felt relieved, [sic] and mad. I was glad I went through it and that it was all over for a while.” After the fighting subsided Woodward’s mind could not help, but wander. He described thinking “plenty about home, maybe too much. At first I couldn’t believe I was here. I thought it was a bad dream . . . I wanted it to be. I went over my entire life. The thought came to me that I was making history and I laughed. Why didn’t they attack? How long wiuld [sic] I be here? . . . Let’s see, 4 points a month . . . How cold would it get this winter? What are patrols like? What are they doing back in Conway? I didn’t want to be here. But there’s a job to do, and I’ll do the best I can. That’s all anyone can do, I guess.” [20a]

Wounded in Action - Killed in Action

Korean War Casualties from Horry County

The official record of Korean War fatalities is incomplete making many local veterans forgotten soldiers of a ‘forgotten war.’ However, the evidence of their existence and sacrifices remain in cemeteries, and archives across the county and state. The sacrifices of some Korean War veterans like Harold D. Woodbury being “born and reared” in Horry County are merely logged as deaths from neighboring counties like Mullins in Woodbury’s case. [17] However, some local veterans have been left out of the official record completely with no evidence of their sacrifice listed among the casualties of South Carolina. The root cause of this regrettable absence is unknown, and most likely will never be determined. Nevertheless, the newspaper clippings below (their information being confirmed through census, and military enlistment documents) contain accounts of these lost veterans’ sacrifices in chronological order as the people of Horry County during the Korean War would have been exposed to them. The deaths of Herbert Thompkins, Isaac Rheuark, Eunice Israel, Nolan Dix, and Hover Johnson are chronicled in the clippings displayed below, yet the record of their sacrifices have seemingly slipped through the cracks. Given the fact that these five veterans have been left off the official record it is safe to assume that there remain even more men whose service is omitted from history. Be that as it may the narratives of some local Korean War veterans either having suffered fatal or non-fatal injuries were covered in local newspapers allowing historians and everyday citizens alike to look back on the heartbreaking news that once gripped the attention of Horry County citizens.

Front page article from The Field (1950)

Woodbury is listed as a fatal casualty from Marion County.

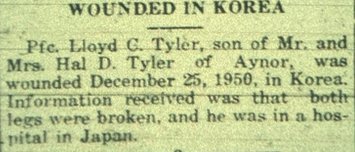

Article from The Horry Herald (1951)

Article from The Field (1951)

Article from The Myrtle Beach Sun (1951)

Article from The Field (1951)

Article from The Myrtle Beach Sun (1951)

Article from The Field (1952)

Article from The Field (1952)

Article from The Horry Herald (1950)

Front page article from The Field (1950)

Article from The Horry Herald (1951)

Article from The Field (1951)

Article from The Myrtle Beach Sun (1951)

Prisoners of War

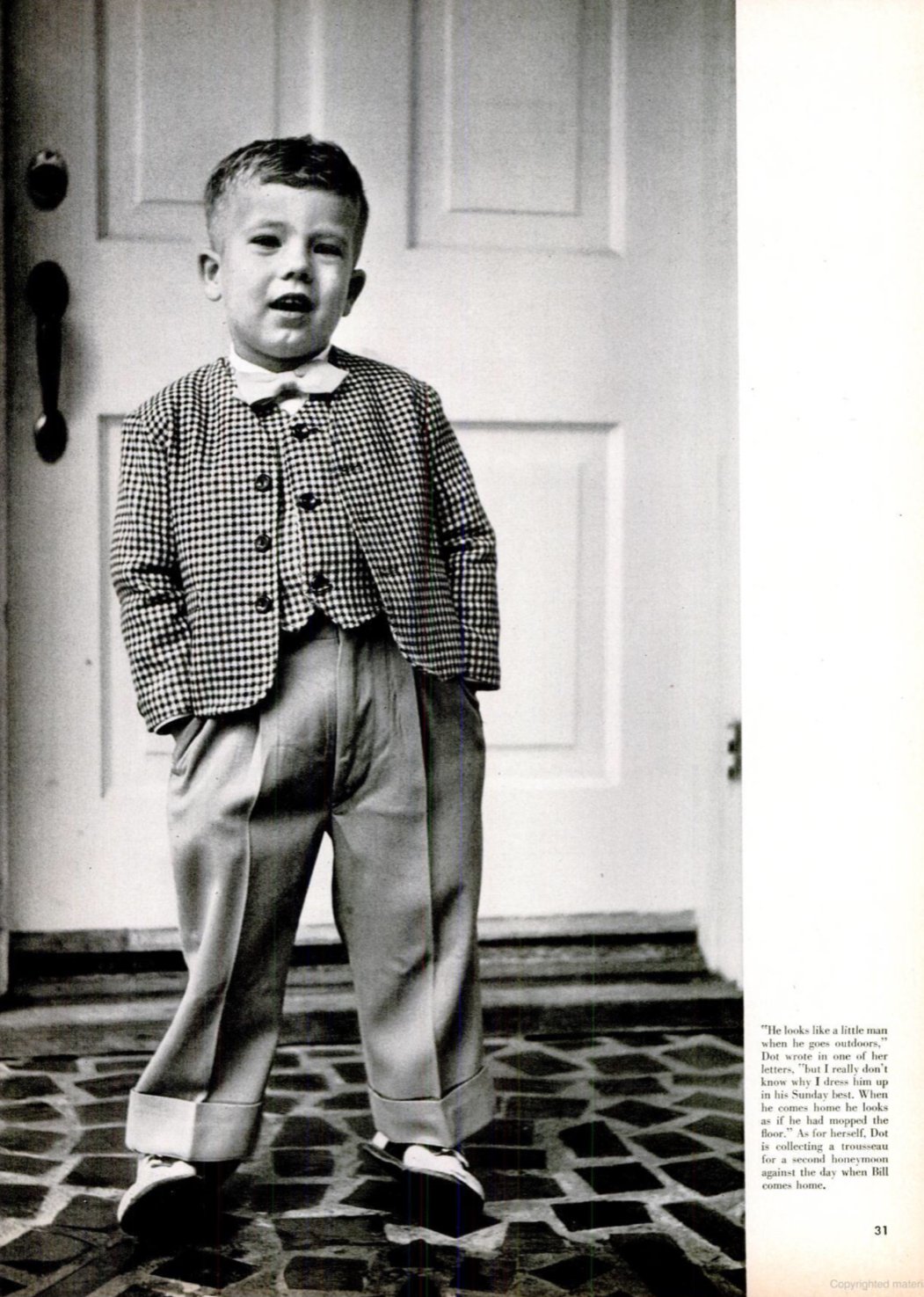

For those dealing with the deaths of loved ones that were killed in action during the Korean War there was somewhat of a silver lining in the fact that families of fallen soldiers could bury their sons close to home and begin the process of grieving. However, for some Horry County residents their suffering was entrenched with a sense of uncertainty, and it was much more prolonged than those whose loved ones met a final end. Numerous Korean War veterans from Horry County were taken as prisoners of war by the North Koreans or Chinese which some may argue was worse than death. Some local veterans like Daniel P. Thompkins (of no relation to Sgt. Herbert Thompkins), would go on to endure years as Prisoners of War in Korea where they would experience unimaginable brutalities and horrors at the hands of their North Korean and Chinese captors. [38] Unlike the narratives of the deaths of local Korean War veterans and their surviving families, the lived experiences of families whose loved ones were captured during the Korean War garnered national attention. The wife and son of American POW Lt. George M. Beale were the central focus of a five page article of within a April, 1953 edition of Life Magazine which covered his wife Dot Beale’s struggle to raise their child and navigate daily life alone without the help of her husband or even knowing if her husband was still alive. [38]The Beale family’s story is just once of many that existed within Horry County during the conflict in Korea, and the families of Korean War POWs struggled with the harsh realities of war every day that the conflict raged on.

Article from The Myrtle Beach Sun (1953)

Article in Life Magazine (1953)

Article from The Field (1951)

Article in Life Magazine (1953)

Article from The Field (1951)

Oral history of local Korean War POW Daniel P. Thompkins (2016)

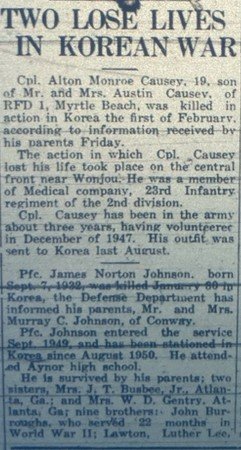

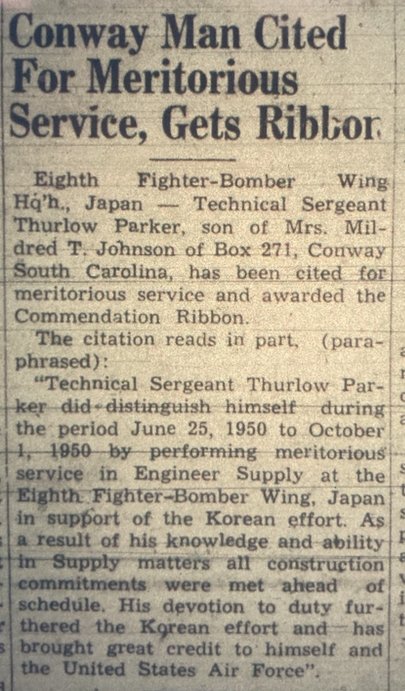

Horry County Locals’ Actions in Korea

Leading daily’s in Horry County eagerly included the narratives of local boys taking the fight to Communists in Korea, and it projected a sense of pride onto the people of Horry County who were able to learn more about their local heroes. The military has been something very near and dear to the hearts of the people of South Carolina for centuries, and to see the names of local men displaying their valor and courage in battle is something that was very special to locals in the 1950s. Not only did these military men bring a sense of honor to their families, but the same was also true for the people of Horry County. Many on the South Carolina Homefront either grew up with or were family friends of the boys in the service, so when news came from Korea it was always the talk of the town. While surely hundreds of men were recognized for their service in Korea only the narratives of a handful of men made it into the local papers, and the target audience of the paper affected who’s narratives were included and who was left out.

Article from The Myrtle Beach Sun (1950)

Article from The Field (1951)

Article from The Field (1951)

Article from The Field (1951)

Article from The Field (1951)

Article from The Field (1951)

Article from The Myrtle Beach Sun (1952)

Article from The Myrtle Beach Sun (1952)

Article from The Myrtle Beach Sun (1952)

Article from The Myrtle Beach Sun (1952)

Article from The Myrtle Beach Sun (1952)

Article from The Horry Herald (1950)

Article from The Horry Herald (1950)

Article from The Field (1951)

Article from The Field (1951)

Article from The Myrtle Beach Sun (1951)

Article from The Myrtle Beach Sun (1951)

Article from The Myrtle Beach Sun (1952)

Article from The Field (1952)

Article from The Myrtle Beach Sun (1952)

Article from The Field (1953)