The War at Home

Cartoon from The Myrtle Beach Sun (1951)

Sign located in the Horry County Museum in Conway, South Carolina

Headline about the funeral of local veteran Mack J. Blackmon’s death in The Field (1951)

Article from The Horry Herald (1950)

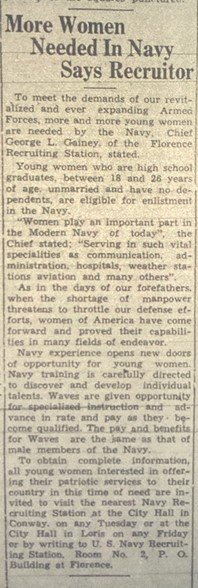

Article from The Field (1951)

Article from The Myrtle Beach Sun (1951)

Article from The Field (1951)

Article from The Field (1951)

Article from The Myrtle Beach Sun (1952)

The conflict in Korea never made it anywhere close to the mainland United States, let alone South Carolina. However, that does not mean that the people of South Carolina were unaffected by the war, or that locals did not interact with the military on a daily, and weekly basis. Early on in the war the people of Horry County experienced the harsh realities of war firsthand. In July, 1950 members of the National Guard from all across the United States Southeast were conducting a two-week training exercise at the deactivated Myrtle Beach Air Base. At the conclusion of training exercises on July 23, 1950 shortly after 10:00 a.m. 39 soldiers took off from the Myrtle Beach Air Base on a twin-engine Curtiss C-46 Commando transport aircraft en route to Tennessee. [1] However, no more than five minutes after takeoff one of the plane’s engines failed, and the plane began to nosedive until it crashed, and exploded “about twelve miles from Myrtle Beach just 400 yards off the main coastal highway,” (the official report states that the crash was at 10:22 a.m. 1.9 miles West of Myrtle Beach). [1] Hundreds of locals witnessed the crash itself, and local man Jim Johnson “ran to the clearing, but the intense heat of the fire drove him back,” when interviewed by the New York Times he remarked that “you could see right away, nobody could have lived through that awful thing.” [1] After the crash “police from Conway and Myrtle Beach and Air Force Military Police later cordoned off the field littered with ashes, bodies and still hot fragments of metal. Mosquitoes swarming out of the low-country swamps plagued the crews trying to recover the bodies. Light rain started to fall although it had been clear at the time of the crash. Persons heard the crash over a twenty-mile area and hundreds rushed to the scene, including the entire congregation of a rural church.” [1] The Myrtle Beach Sun when covering the incident explained that there was a general consensus among the people of Horry County that even although “none of the victims were from this city or even near by [sic] communities. But the accident had no less effect on residents of Myrtle Beach than on Nashville, home town [sic] of the Guardsmen,” and that “the death of these men, many of them not yet out of their teens, reminds us anew of the tragedy of wars. For they were the victims of war as much as if they had died in the Korean fighting. It matters not that they were only training to fight and had not yet reached the battlelines [sic]… the lives cannot be reclaimed but they will long be remembered in the hearts of the people of this community.” [14] The crash was the classified eighth worst airline accident in the United States at the time (it is currently the fourteenth worst in American history), and while contemporary reports vary the official number of casualties amounted to all four crew members who were members of the National Guard from Florida and the remaining 35 passengers all from the Tennessee National Guard were killed.

Americans were fearful over the possibility of a nuclear attack from Russia; the media and government were both preparing the American public for these sorts of attacks. Locals were pounded with information about civil defense, and safety drills like Duck and Cover being practiced in local schools were the norm. Basements are not prevalent in South Carolina, thus there are no known underground fallout shelters in Horry County like we see in other parts of the United States. However public buildings like the Conway Post Office were often designated as fallout shelters (see picture to the left). In the event of a nuclear attack near Horry County there was little chance that the local post office was going to protect anyone from the blast or nuclear fallout, but most local residents during the Korean War had some sort of plan or idea of what to they were going to do in the event of a nuclear attack from abroad. These fears and the perception that there was a great threat of an attack from abroad made the Korean War much more of a present danger for locals who were increasingly being exposed to anti-communists propaganda, and sensationalism in the media.

Article from The Horry Herald (1950)

Draft list from The Myrtle Beach Sun (1952)

Article from The Myrtle Beach Sun (1951)

Koreans and Chinese in South Carolina

Pictured above are “Mr. and Mrs. Don M. Kim of Seoul, South Korea” who were studying Christianity in South Carolina “in prepartation of their Christian service in their native county, Korea.” They made weekend appearances at a number of churches in Conway shortly after the Korean War began. [14]

Headline and photograph from The Myrtle Beach Sun (1950)

Pictured above at a United Nations Day event at Winthrop College are Josie King from China (far left), Miriam Mizumo from Tokyo, Japan (second from the right), and Bo Gyung Jung (far right) an orphan from Seoul, South Korea were all studying at Winthrop College in Rock Hill, South Carolina during the 1951-1952 school year on an academic scholarship. Bo’s attendance at the university was delayed by the outbreak of the war in Korea. Four other girls Irene Yao-ming Shaw, Una Yu-lien Chich, Mary Li, Keng-ting Helen Chuan, and Keng-ping Marian Chuan (twins) from China are not pictured.

Picture and from Winthrop College’s The Johnsonian (1952)

Everyday Life

Plans to establish a junior college in Conway, South Carolina, and what would become Coastal Carolina University began during the Korean War. Original plans for the proposed junior college included an recruitment of an inaugural class that included graduates of Horry County Schools, and Korean War Veterans. The junior college would be open to white students only.

Article from The Myrtle Beach Sun (1953)

News of flying saucers, and rumored explosions in Horry County invaded the front covers of newspapers and garnered national attention for weeks during the Korean War. Loyd C. Booth of Poplar, South Carolina claimed to have shot a flying saucer above his homestead, and a few days after the incident explosions were heard near Loris, South Carolina. Events such as these can be attributed to a number of factors, one of which being hysteria and fear of unknown Communist technology.

Article from The Myrtle Beach Sun (1953)

Article from The Myrtle Beach Sun (1952)

Article from The Myrtle Beach Sun (1953)

Ad from The Myrtle Beach Sun (1951)

Entering the Modern Era

Ad from The Myrtle Beach Sun (1950)

Headline from The Myrtle Beach Sun (1951)

Ad from The Myrtle Beach Sun (1950)

Article from The Myrtle Beach Sun (1951)

Ad from The Myrtle Beach Sun (1951)

Movie Ad from The Field (1951)

Article from The Field (1951)

The Roaring 20’s are most often described as a time where Americans were becoming increasingly modern with the newest technologies of the time. Whereas in Horry County the late 1940s, and early 1950s were the years in which the affects of modernization were most impactful. Some modern technologies like motor vehicles, and locomotives were common in the region other technologies like television, telephone, and AC where much less common prior to the 1950s. [31] While today the residents of Horry County often take their electric fans, and HVAC systems for granted, heating and air conditioning was just coming into widespread prevalence in the area during the years leading up to and during the Korean War. Greater access to AC to fend off the humid South Carolina summers finally made living in the region bearable for most people; this partially contributed to the influx of people into the Horry County. Between 1940 and 1950 the population of Horry County grew by over 15% with Conway growing by 20.1%, Loris growing by 29.6%, and Myrtle Beach more than doubling in size growing at a whopping 105.8% in those ten years. [41] This influx of people into Horry County led to a greater need and demand for access to electricity, television, radio, and telephone among other luxuries. In order to meet this demand, and tap into this expanding market in the county the Horry Telephone Cooperative (HTC) was founded March 5, 1952 in the midst of the Korean War. [31] HTC began servicing population centers like Loris, Myrtle Beach, and Conway heavily in the early years, but uproar over lack of service to more rural areas of the county led to increased access to television, telephone, and radio to even the most remote of areas. [31] With greater access to information technology came a much more informed and educated populace. In the years leading up to the Korean War in Horry County for most people the majority if not all of their news, and worldview came from the local newspaper and nothing more. However, the influx of television, radio, and telephones in people’s homes exposed locals to a greater variety of media that would ultimately go to to change family dynamics, social lives, and certainly help shape the public opinion of the local population.

Ad from The Myrtle Beach Sun

Film line-up in The Field (1951)

Radio gave the people of Horry County greater access to information, and local officials used the radio as a platform in times of crisis. In the above article it is shown how Sheriff C.E Sasser utilized radio to discredit the Ku Klux Klan.

Article from The Field (1951)